'Conservative Whip Jay Hill spoke of a recent dinner he and his wife had with Afghanistan's ambassador to Canada, who was interrupted by a phone call.

"I could see he was upset," said Mr. Hill, adding that he asked why. "Two young girls were murdered on the roadside while walking home from school. What was their crime? Their crime was that they wanted an education. ...

"To me, the discussion that night very clearly exemplified why we are there."'

Breaking News

the Globe and Mail

Wednesday, February 27

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

"The First Afghan War provided the clear lesson to the British authorities that while it may be relatively straightforward to invade Afghanistan...

...it is wholly impracticable to occupy the country or attempt to impose a government not welcomed by the inhabitants. The only result will be failure and great expense in treasure and lives."

The Battle of Kabul and the retreat to Gandamak

War: First Afghan War

Date: January 1842.

Place: Central Afghanistan.

Combatants: British and Indians of the Bengal Army and the army of Shah Shuja against Afghans and Ghilzai tribesmen..

Afghans attacking the retreating British and Indian army

Generals: General Elphinstone against the Ameers of Kabul, particularly Akbar Khan, and the Ghilzai tribal chiefs.

Size of the armies: 4,500 British and Indian troops against an indeterminate number of Ghilzai tribesmen, possibly as many as 30,000.

Uniforms, arms and equipment:The British infantry, wearing cut away red jackets, white trousers and shako hats, were armed with the old Brown Bess musket and bayonet. The Indian infantry were similarly armed and uniformed.

The Ghilzai tribesmen carried swords and jezail, long barrelled muskets.

Winner: The British and Indian force was wiped out other than a small number of prisoners and one survivor.

British Regiments: 44th Foot, later the Essex Regiment and now the Royal Anglian Regiment. Regiments of the Bengal Army:2nd Bengal Light Cavalry1st Bengal European Infantry37th Bengal Native Infantry48th Bengal Native Infantry2nd Bengal Native Infantry27th Bengal Native Infantry.Bengal Horse Artillery

The War: The British colonies in India in the early 19th Century were held by the Honourable East India Company, a powerful trading corporation based in London, answerable to its shareholders and to the British Parliament.

In the first half of the century France as the British bogeyman gave way to Russia, leading finally to the Crimean War in 1854. In 1839 the obsession in British India was that the Russians, extending the Tsar’s empire east into Asia, would invade India through Afghanistan.

This widely held obsession led Lord Auckland, the British governor general in India, to enter into the First Afghan War, one of Britain’s most ill-advised and disastrous wars.

Until the First Afghan War the Sirkar (the Indian colloquial name for the East India Company) had an overwhelming reputation for efficiency and good luck. The British were considered to be unconquerable and omnipotent. The Afghan War severely undermined this view. The retreat from Kabul in January 1842 and the annihilation of Elphinstone’s Kabul garrison dealt a mortal blow to British prestige in the East only rivaled by the fall of Singapore 100 years later.

The causes of the disaster are easily stated: the difficulties of campaigning in Afghanistan’s inhospitable mountainous terrain with its extremes of weather, the turbulent politics of the country and its armed and refractory population and finally the failure of the British authorities to appoint senior officers capable of conducting the campaign competently and decisively.

The substantially Hindu East India Company army crossed the Indus with trepidation, fearing to lose caste by leaving Hindustan and appalled by the country they were entering. The troops died of heat, disease and lack of supplies on the desolate route to Kandahar, subject, in the mountain passes, to constant attack by the Afghan tribes. Once in Kabul the army was reduced to a perilously small force and left in the command of incompetents. As Sita Ram in his memoirs complained: “If only the army had been commanded by the memsahibs all might have been well."

The disaster of the First Afghan War was a substantial contributing factor to the outbreak of the Great Mutiny in the Bengal Army in 1857.

The successful defence of Jellalabad and the progress of the Army of Retribution in 1842 could do only a little in retrieving the loss of the East India Company’s reputation.

Account: Following the British capture of Kandahar and Ghuznee Dost Mohammed, whose replacement on the throne in Kabul by Shah Shujah was the purpose of the British expedition into Afghanistan, despairing of the support of his army fled to the hills. On 7th August 1839 Shah Shujah and the British and Indian Army entered Kabul. The British official controlling the expedition was Sir William Macnaghten, the Viceroy’s Envoy, acting with his staff of political officers.

At first all went well. British money and the powerful Anglo-Indian Army kept the Afghan tribes in controllable bounds, pacifying the Ameers with bribes and forays into the surrounding districts.

In November 1840 during a raid into Kohistan two squadrons of Bengal cavalry failed to follow their officers in a charge against a small force of Afghans led by Dost Mohammed himself. Soon afterwards, despairing of his life in the mountains, Dost Mohammed surrendered to Macnaghten and went into exile in India, escorted by a division of British and Indian troops no longer required in Afghanistan and accompanied by the commander in chief Sir Willoughby Cotton.

In December 1840 Shah Shujah and Macnaghten withdrew to Jellalabad for the ferocious Afghan winter, returning to Kabul in the spring of 1841.

In the assumption that the establishment of Shah Shujah as Ameer was complete, the British and Indian troops were required to move out of the Balla Hissar, a fortified palace of considerable strength outside Kabul, and build for themselves conventional cantonments. A further complete brigade of the force was withdrawn, leaving the remaining regiments to settle into garrison life as if in India, summoning families to join them, building a race course and disporting themselves under the increasingly menacing Afghan gaze.

There were plenty of signs of trouble. The Ghilzai tribes in the Khyber repeatedly attacked British supply columns from India. Tribal revolt made Northern Baluchistan virtually ungovernable. Shah Shujah’s writ did not run outside the main cities, particularly in the South Western areas around the Helmond River.Sir William Cotton was replaced as commander in chief of the British and Indian forces by General Elphinstone, an elderly invalid now incapable of directing an army in the field, but with sufficient spirit to prevent any other officer from exercising proper command in his place.

The fate of the British and Indian forces in Afghanistan in the winter of 1840 to 1841 provides a striking illustration of the collapse of morale and military efficiency where the officers in command are indecisive and wholly lacking in initiative and self-confidence. The only senior officer left in Afghanistan with any ability was Brigadier Nott, the garrison commander at Kandahar. Crisis struck in October 1841. In that month Brigadier Sale took his brigade out of Kabul as part of the force reductions and began the march through the mountain passes to Peshawar and India. Throughout the journey his column was subjected to continuing attack by Ghilzai tribesmen and the armed retainers of the Kabul Ameers. Sale’s brigade, which included the 13th Foot, fought through to Gandamak, where a message was received summoning the force back to Kabul, Sale did not comply with the order and continued to Jellalabad.

In Kabul serious trouble had broken out. On 2nd November 1841 an Afghan mob stormed the house of Sir Alexander Burnes, one of the senior British political officers, and murdered him and several of his staff. It is the authoritative assessment that if the British had reacted with vigour and severity the Kabul rising could have been controlled. But such a reaction was beyond Elphinstone’s abilities. All he could do was refuse to give his deputy, Brigadier Shelton, the discretion to take such measures. Until the end of the year the situation of the Kabul force deteriorated as the Afghans harried them and deprived them of supplies and pressed them more closely.

On 23rd December 1841 Macnaghten was lured to a meeting with several Afghan Ameers and murdered. While the Kabulis awaited a swift retribution the British and Indian regiments cowered fearful in their cantonments. Attempts to clear the high ground that enabled the Afghans to dominate the cantonments failed miserably, because the troops were too cowed to be capable of aggressive action.

The beginning of the end came on 6th January 1842 when the British and Indian garrison, 4,500 soldiers, including 690 Europeans, and 12,000 wives, children and civilian servants, following a purported agreement with the Ameers guaranteeing safe conduct to India, marched out of the cantonments and began the terrible journey to the Khyber Pass and on to India. As part of the agreement with the Ameers all the guns had to be left to the Afghans except for one horse artillery battery and 3 mountain guns and a number of British officers and their families were required to surrender as hostages, taking them from the nightmare slaughter of the march into relative security. In spite of the binding undertaking to protect the retreating army, the column was attacked from the moment it left the Kabul cantonments.

The army managed to march 6 miles on the first day. The night was spent without tents or cover, many troops and camp followers dying of cold. The next day the march continued, Brigadier Shelton, after his ineffectiveness as Elphinstone’s deputy, showing his worth leading the counter attacks of the rearguard to cover the main body.

At Bootkhak the Kabul Ameer, Akbar Khan, arrived claiming he had been deputed to ensure the army completed its journey without further harassment. He insisted that the column halt and camp, extorting a large sum of money and insisting that further officers be given up as hostages. One of the conditions negotiated with the Ameers was that the British abandon Kandahar and Jellalabad. Akbar Khan required the hostages to ensure Brigadier Sale left Jellalabad and withdrew to India.

The next day found the force so debilitated by the freezing night that few of the soldiers were fit for duty. The column struggled into the narrow five mile long Khoord Cabul pass to be fired on for its whole length by the tribesmen posted on the heights on each side. The rearguard was found by the 44th Regiment who fought to keep the tribesmen at bay. 3,000 casualties were left in the gorge.

On 9th January 1842 Akbar Khan required further hostages in the form of the remaining married officers with their families. For the next two days the column pushed through the passes and fought off the incessant attacks of the tribesmen. On the evening of 11th January 1842 Akbar Khan compelled General Elphinstone and Brigadier Shelton to surrender as hostages, leaving the command to Brigadier Anquetil. The troops reached the Jugdulluk crest to find the road blocked by a thorn abattis manned by Ghilzai tribesmen. A desperate attack was mounted, the horse artillery driving their remaining guns at the abattis, but few managed to pass this fatal obstruction.

The final stand took place at Gandamak on the morning of 13th January 1842 in the snow. 20 officers and 45 European soldiers, mostly of the 44th Foot, found themselves surrounded on a hillock. The Afghans attempted to persuade the soldiers that they intended them no harm. Then the sniping began followed a series of rushes. Captain Souter wrapped the colours of the regiment around his body and was dragged into captivity with two or three soldiers. The remainder were shot or cut down. Only 6 mounted officers escaped. Of these 5 were murdered along the road. On the afternoon of 13th January 1842 the British troops in Jellalabad, watching for their comrades of the Kabul garrison, saw a single figure ride up to the town walls. It was Dr Brydon, the sole survivor of the column.

Casualties: The entire force of 690 British soldiers, 2,840 Indian soldiers and 12,000 followers were killed or in a few cases taken prisoner. The 44th Foot lost 22 officers and 645 soldiers, mostly killed. Afghan casualties, largely Ghilzai tribesmen, are unknown.

Follow-up: The massacre of this substantial British and Indian force caused a profound shock throughout the British Empire. Lord Auckland, the Viceroy of India, is said to have suffered a stroke on hearing the news. Brigadier Sale and his troops in Jellalabad for a time contemplated retreating to India, but more resolute councils prevailed, particularly from Captains Broadfoot and Havelock, and the garrison hung on to act as the springboard for the entry of the “Army of Retribution” into Afghanistan the next year.

Regimental anecdotes and traditions:

The First Afghan War provided the clear lesson to the British authorities that while it may be relatively straightforward to invade Afghanistan it is wholly impracticable to occupy the country or attempt to impose a government not welcomed by the inhabitants. The only result will be failure and great expense in treasure and lives.

The British Army learnt a number of lessons from this sorry episode. One was that the political officers must not be permitted to predominate over military judgments. The War provides a fascinating illustration of how the character and determination of its leaders can be decisive in determining the morale and success of a military expedition.

It is extraordinary that officers, particularly senior officers like Elphinstone and Shelton, felt able to surrender themselves as hostages, thereby ensuring their survival, while their soldiers struggled on to be massacred by the Afghans.

[....and equally interesting that American officers get helicoptered out of harm's way

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/24/magazine/24afghanistan-t.html?_r=1&ex=1361509200&en=2af41ac16189c49d&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss&pagewanted=all&oref=slogin

while their troops fight their way through an Afghan ambush...]

References:Afghanistan From Darius to Amanullah by Lieutenant General Sir George McMunn.

The Afghan Wars by Archibald Forbes.© britishbattles.com 2005.

© britishbattles.com 2007.

Sunday, February 24, 2008

NATO: Eulogy for a Burial at Sea

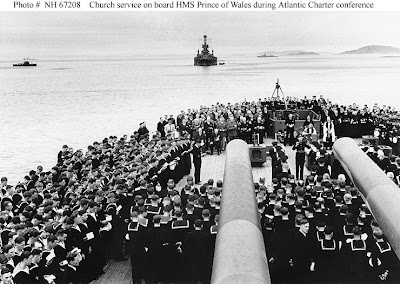

We are gathered together in Placentia Bay in 2011 where, 70 years ago, Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt wrote the first draft of the Atlantic Charter, subsequently the basis for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Our purpose today is to acknowledge that their goals have been fulfilled, and that protection of humanity from the scourge of war must pass into other hands. So it must be, or the purposes of Churchill and Roosevelt will be denied and defeated.

NATO itself has become, like Frankenstein, an organism beyond the imagination of its creators, a parallel organization to the United Nations, yet providing neither the peace nor the security long hoped for.

The attacks on September 11, 2001, aroused in the United States a desire to act alone. Under these circumstances, we must recall the words of George Orwell: "There is only one rule in power politics, and that is that there are no rules".

In times such as these, NATO has become an enabler of power politics. It has played its part, and we now consign it to the deeps. May the Lord have mercy on its intentions.

Our purpose today is to acknowledge that their goals have been fulfilled, and that protection of humanity from the scourge of war must pass into other hands. So it must be, or the purposes of Churchill and Roosevelt will be denied and defeated.

NATO itself has become, like Frankenstein, an organism beyond the imagination of its creators, a parallel organization to the United Nations, yet providing neither the peace nor the security long hoped for.

The attacks on September 11, 2001, aroused in the United States a desire to act alone. Under these circumstances, we must recall the words of George Orwell: "There is only one rule in power politics, and that is that there are no rules".

In times such as these, NATO has become an enabler of power politics. It has played its part, and we now consign it to the deeps. May the Lord have mercy on its intentions.

Thursday, February 21, 2008

A National Disgrace

Cheating our veterans

Sean Bruyea, National Post Published: Thursday, February 14, 2008

This Valentine's Day, thousands of cards and good wishes will be sent to soldiers on the front lines in Afghanistan. But back home, a very different sentiment is being shown to more than 4,200 injured soldiers. While Canadians honour and thank our soldiers serving abroad, many disabled military members are forgotten once their uniforms come off.

Since October, 2000, Canadian law stipulates that a wounded soldier can collect his full salary as well as pain and suffering payments. If a soldier is so wounded as to be unemployable, he must be forced out of the military and paid a salary reduced to 75% of his previous income -- with pain-and-suffering payments deducted from the new, lower income. The injustice of this deduction policy attracted the attention of the standing committee on national defence and veterans affairs in 2003, which passed a motion imploring the minister of national defence to stop the deductions. Ironically, the current minister of national defence, Peter MacKay, as well as the current prime minister, president of the treasury board and minister of veterans affairs were all associate members of that committee when the motion was passed.

And yet nothing has been done to right this wrong. The reason is simple: The bureaucrats standing in the way of a just policy have little idea what it means to serve in the military. Ironically, these same senior bureaucrats receive free disability plans, paid for by Canadian taxpayers -- and their plan does not deduct pain and suffering payments.

Since Tuesday, a Halifax courtroom has been hearing a request to certify a class-action lawsuit that would force the federal government to stop deducting pain-and-suffering payments from disabled soldiers' long-term disability plans. The judge has read an affidavit from Andre Bouchard, the president of the Service Income Security Insurance Plan (SISIP), the disability plan mandatory for all Canadian forces personnel. Mr. Bouchard, who in fact served in the military for almost 30 years, claims that should the SISIP plan stop deducting pain and suffering payments, the result would be "exorbitant premiums which would impose significant hardship on the members of the Canadian Forces."

But how much more expensive would the higher premiums actually be? Currently, a corporal in the military pays approximately $9.40 per month for the long-term disability policy. Mr. Bouchard predicts that premiums would increase by 40%, or just $3.76 per month-- the price of a latte.

Mr. Bouchard makes further excuses, claiming that disabled soldiers "could effectively receive more than 100% of their former income" were the policy to be changed. But a senior federal public servant on rehabilitation can earn up to 100% of his former income -- and still collect veterans affairs payments if previously injured in the military. Why the double standard?

Such obvious discrimination led the previous department of national defence ombudsman Yves Cote to state "the inequity might very well be serious enough to attract the protection of human rights legislation, as well as the protection of the equality provisions set out in section 15 the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which identify physical and mental disabilities as prohibited grounds of discrimination."

Canada must renew the broken trust with our forgotten soldiers and give them back the money that has been wrongfully taken from them. Only then will the soldiers consider trusting the very society for which they have sacrificed so much.

seankis@rogers.com - Sean Bruyea is a retired captain and disabled soldier who served as an intelligence officer in the Canadian Forces for 14 years. He is now an advocate for other disabled veterans.

Sean Bruyea, National Post Published: Thursday, February 14, 2008

This Valentine's Day, thousands of cards and good wishes will be sent to soldiers on the front lines in Afghanistan. But back home, a very different sentiment is being shown to more than 4,200 injured soldiers. While Canadians honour and thank our soldiers serving abroad, many disabled military members are forgotten once their uniforms come off.

Since October, 2000, Canadian law stipulates that a wounded soldier can collect his full salary as well as pain and suffering payments. If a soldier is so wounded as to be unemployable, he must be forced out of the military and paid a salary reduced to 75% of his previous income -- with pain-and-suffering payments deducted from the new, lower income. The injustice of this deduction policy attracted the attention of the standing committee on national defence and veterans affairs in 2003, which passed a motion imploring the minister of national defence to stop the deductions. Ironically, the current minister of national defence, Peter MacKay, as well as the current prime minister, president of the treasury board and minister of veterans affairs were all associate members of that committee when the motion was passed.

And yet nothing has been done to right this wrong. The reason is simple: The bureaucrats standing in the way of a just policy have little idea what it means to serve in the military. Ironically, these same senior bureaucrats receive free disability plans, paid for by Canadian taxpayers -- and their plan does not deduct pain and suffering payments.

Since Tuesday, a Halifax courtroom has been hearing a request to certify a class-action lawsuit that would force the federal government to stop deducting pain-and-suffering payments from disabled soldiers' long-term disability plans. The judge has read an affidavit from Andre Bouchard, the president of the Service Income Security Insurance Plan (SISIP), the disability plan mandatory for all Canadian forces personnel. Mr. Bouchard, who in fact served in the military for almost 30 years, claims that should the SISIP plan stop deducting pain and suffering payments, the result would be "exorbitant premiums which would impose significant hardship on the members of the Canadian Forces."

But how much more expensive would the higher premiums actually be? Currently, a corporal in the military pays approximately $9.40 per month for the long-term disability policy. Mr. Bouchard predicts that premiums would increase by 40%, or just $3.76 per month-- the price of a latte.

Mr. Bouchard makes further excuses, claiming that disabled soldiers "could effectively receive more than 100% of their former income" were the policy to be changed. But a senior federal public servant on rehabilitation can earn up to 100% of his former income -- and still collect veterans affairs payments if previously injured in the military. Why the double standard?

Such obvious discrimination led the previous department of national defence ombudsman Yves Cote to state "the inequity might very well be serious enough to attract the protection of human rights legislation, as well as the protection of the equality provisions set out in section 15 the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which identify physical and mental disabilities as prohibited grounds of discrimination."

Canada must renew the broken trust with our forgotten soldiers and give them back the money that has been wrongfully taken from them. Only then will the soldiers consider trusting the very society for which they have sacrificed so much.

seankis@rogers.com - Sean Bruyea is a retired captain and disabled soldier who served as an intelligence officer in the Canadian Forces for 14 years. He is now an advocate for other disabled veterans.

Tuesday, February 19, 2008

NATO soldier killed in explosion in southern Afghanistan

NATO update

http://www.nato.int/isaf/docu/pressreleases/2008/02-february/pr080221-076.html

Meanwhile, a NATO soldier was killed and another wounded in an explosion in southern Afghanistan while two suspected Taliban leaders were killed and 22 others militants were detained.

The soldiers were patrolling in Viking vehicles to disrupt Taliban forces north of Sangin in the southern Helmand province when the explosion occurred, British defence ministry said in a statement.

NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) also confirmed the death of one of its soldiers and the wounding of another, but provided no more details.

The deceased soldier became the 89th British fatality since the ouster of Taliban in late 2001 in Afghanistan. There are about 7,800 British soldiers deployed mainly to southern Helmand province, which is also the largest-opium-growing province in the country.

http://www.nato.int/isaf/docu/pressreleases/2008/02-february/pr080221-076.html

Meanwhile, a NATO soldier was killed and another wounded in an explosion in southern Afghanistan while two suspected Taliban leaders were killed and 22 others militants were detained.

The soldiers were patrolling in Viking vehicles to disrupt Taliban forces north of Sangin in the southern Helmand province when the explosion occurred, British defence ministry said in a statement.

NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) also confirmed the death of one of its soldiers and the wounding of another, but provided no more details.

The deceased soldier became the 89th British fatality since the ouster of Taliban in late 2001 in Afghanistan. There are about 7,800 British soldiers deployed mainly to southern Helmand province, which is also the largest-opium-growing province in the country.

The Quick and the Dead

http://www.antiwar.com/orig/kitson.php?articleid=12379

I should explain that the "quick" is from the King James version of the Bible, meaning the "living".

I should explain that the "quick" is from the King James version of the Bible, meaning the "living".

Jus ad bellum et jus in bello

Robert Kolb is preparing a doctorate in international law at the Graduate Institute for International Studies in Geneva; his thesis is entitled La bonne foi en droit international public (Good faith in public international law).

The august solemnity of Latin confers on the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello [1] the misleading appearance of being centuries old. In fact, these expressions were only coined at the time of the League of Nations and were rarely used in doctrine or practice until after the Second World War, in the late 1940s to be precise. This article seeks to chart their emergence.The doctrine of just warThe terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello did not exist in the Romanist and scholastic traditions. They were unknown to the canon and civil lawyers of the Middle Ages (glossarists, counsellors, ultramontanes, doctors juris utriusque, etc.), as they were to the classical authorities on international law (the School of Salamanca, Ayala, Belli, Gentili, Grotius, etc.). In neither period, moreover, was there a separation between two sets of rules — one ad bellum, the other in bello. [2]From earliest times, the Western tradition sought to place war in a legal framework by formulating a doctrine of just war [3]. The aim was to reconcile might and right, Sein and Sollen, by making the former serve the latter, or by curtailing might with right. On the basis of those premises, war was seen as a just response to unprovoked aggression, and more generally as the ultimate means for restoring a right that had been violated (consecutio juris) [4] or for punishing the offender [5]. The material causes for which a just war could be waged fell into four categories: defence, recuperation of property, recovery of debts and punishment. An act of war was considered lawful if it was just; and it was considered just if it met the conditions enumerated above.In the doctrine of bellum justum, therefore, legal analysis bore exclusively on the act of resorting to war, and more particularly on the causes pursued.

War was viewed from the subjective angle as a concrete act carried out by a specific belligerent for specific reasons, and such an act brought into being a legal regime that reflected the validity of the causes invoked or, so to speak, the belligerent’s right to resort to force. This meant that war was not seen as a de facto situation to which the same set of rules applied in all cases. In other words, there was no general jus in bello; the rights and obligations of belligerents were unequal and depended exclusively on the causes which they claimed to be pursuing and on the material justness of those causes. [6]

Thus, for example, Grotius’s temperamenta belli (restrictions on warfare), which it is tempting to equate with contemporary jus in bello, applied only to belligerents resorting to war for a just cause [7]; they broadened the concept of just war while defining its limits. Here, too, everything revolved around the notion of just cause. A belligerent without a just cause had no rights; he was simply a criminal who might beexecuted.

Consequently, no legal restraints could be imposed on his behaviour. For these reasons, there was no room for jus in bello as we understand it today, that is, a body of independent, objective and suprapersonal rules applying to all belligerents alike and governing the conduct of hostilities in a de facto situation [8]. This explains why both the term jus in bello and the concept to which it refers are absent from the classical texts.

As for the term jus ad bellum, its absence is more surprising. However, the simple right to wage war that was vested in public authorities was also irrelevant in the doctrine of bellum justum [9]. Legal analysis looked deeper, focusing instead on causes and hence on the lawfulness of resorting to war. Moreover, the predominance of ad bellum considerations in general over the in bello aspect made it impossible even to conceive of such terms, whose existence would have implied a more extensive, evenly balanced and fully articulated development of two mutually exclusive branches of the law [10].

We are reminded of the early philosophers’ theory whereby a term or a concept can come into existence only in relation to its absolute opposite. They claimed, for example, that ugliness existed only in relation to beauty; it could not be conceived of except in contrast to beauty.

Although the time was clearly not ripe for the emergence of the terms that concern us here, they sometimes crept in, used in a non-technical sense far removed from their modern meaning. Grotius, for instance, wrote that he was “fully convinced (...) that there is a law common to all nations governing both recourse to war and the conduct of warfare...” [11]. This law ad bella and in bellis obviously remained subordinate to the doctrine of just war [12]. To sum up, the subjective notion of the right to wage war in pursuit of certain causes precluded the emergence of an independent jus in bello; at the same time, however, the doctrine of lawful causes for waging war inhibited the affirmation of the simple right to make war (jus ad bellum). In such a system, both concepts lay outside the scope of the law, which was concerned with antecedent issues.

War as a de facto situation.

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the doctrine of just war lost ground to the idea that States had discretionary powers to wage war and that those powers could be used as a means of pursuing national policy. That was the era of raison d’Etat. This concept of war became permanently entrenched in the nineteenth century, in parallel with the erosion of the concept of war as a just act. War was now seen as a de facto and intellectually neutral situation [13]. Quite logically, the result was a major shift in the legal emphasis from the subjective lawfulness of resorting to war to the rights and duties relating to hostilities as such, in other words to rights and duties durante bello [14]. This new edifice appears to be a mirror image of the previous one. A system based on the material lawfulness of war (war as a sanction) gave way to a system focusing on its formal regulation (rules pertaining to the opening of hostilities and the effects of war) [15]. To quote an eminent specialist on the subject: “Now that the field of vision had been restricted, greater attention could be paid to the conduct of hostilities: for owing to this indifference [to the causes of war], armed violence came to be seen first and foremost as a process to be regulated in itself, regardless of its causes, motives and ends.” [16]

This opened the door to jus in bello as it is understood today. The distinction which Vitoria had already begun to make between lawful reasons for resorting to war and just limits in the law of war [17] was upheld by Wolff, the first to see rights and duties durante bello as being independent of the underlying causes of war [18], and was later firmly established by Vattel, who incorporated into the law of nations a series of rules setting legal restrictions on means of warfare [19]. Kant made an explicit and modern distinction between the two branches of the law (Recht zum Krieg and Recht im Kriege) [20], but neither he nor any of the other authors mentioned used the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello. The explanation for this lies in the lack of any doctrinal need to draw a conceptual distinction between the two branches of the law rather than in random developments of terminology or the decline of Latin.

The fact is that for reasons that were different in nature but identical as to their effect, the mere competence to resort to war (jus ad bellum) aroused no more legal interest than it had previously. As one of the sovereign’s absolute and discretionary powers [21], it was seen as the cornerstone of the rules of law relating to war, their logical prius, and thus basically remained an implicit dogma. Legal endeavours had focused entirely on the formalities to be observed in initiating hostilities and on the respective rights and obligations of belligerents, that is to say on matters subsequent to the subjective right to resort to war. Yet the term jus in bello was still not used. The lack of any opposition or equivalence between the two branches of the law prevented the emergence of such a term, which could only come into existence when the two aspects of war assumed approximately equal importance and it became necessary to underline the distinction between them.

It was at the time of the League of Nations that the two branches came to be considered on an equal footing and found their place in positive law. In the expression of the time, the aim was to “outlaw war” [22]. The former absolute power to resort to war was replaced by the rules of jus contra bellum. From then on, the problem of recourse to force was at the centre of legal concerns, standing in opposition to law in bello. The theoretical distinction between laws aimed at preventing war and the laws and customs of warfare was thus clearly established. All that remained to be done was to find appropriate terminological expression for this distinction, which had finally crystallized under the pressure of history.

The terminological aspect

Neither in the Middle Ages nor in the Age of Enlightenment did the law lack terms for what is now known as jus in bello. At least certain analogies can be drawn providing the conceptual differences outlined above are taken into account. Many texts from these periods contain terms such as jus belli [23], usus in bello [24], mos et consuetudo bellorum [25], modus belli gerendi [26], forma belli gerendi [27], quid quantumque in bello liceat et quibus modis [28], jus armorum [29], lex armorum [30], jus militare [31], jura et usus armorum [32], droiz de guerre [33], droit d’armes [34], drois, usaiges et coustumes d’armes [35], usance de guerre [36], droit et usage d’armes [37], Kriegsmanier [38], etc [39]. Not all these terms pertain to public international law as we understand it today: they did not apply only to armies set up under public authority. Jus armorum was the professional code for warriors [40] — knights, for example — and constitutes jus gentium. [41]

One important expression in the context of public international law is jura belli, which can be traced back to Livy[42]. In the nineteenth century it was sometimes used to mean jus in bello in the modern sense (Heffter used it this way in his influential handbook) [43]. The Latin terms jura belli and jus belli both seem to have been derived from the Greek expression “oi tou polemou nomoi” used by Polybius [44]. The English expression “laws of war” is also quite old. During the reign of Charles I, the Earl of Essex decreed the Laws and ordinances of war governing the conduct of the parliamentary forces during the civil war that brought Cromwell to power [45]. The term can be found in the literature as well [46]. In French, the expression lois de la guerre rapidly gained acceptance. [47]

It is extremely rare to find the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello used before 1930. Neither was mentioned during the 1899 and 1907 Peace Conferences, among whose aims was codification of the law of war [48]. Enriques used the term jus ad bellum in 1928, having apparently invented it on the spot to serve a specific need[49]. Keydel drew a clear distinction between the two branches of the law in a well-researched thesis on recourse to war published in 1931 in a scholarly review edited by Professor Strupp, but did not use the terms in question [50]. Keydel, like Strupp himself [51], diligently enumerated all the Latin words and expressions relating to the matter. It may be concluded, therefore, that up to the early 1930s the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello had no currency.

They began to gain recognition towards the middle of the decade, in particular, it would seem, at the prompting of the School of Vienna. [52] Among the first to use these terms was Josef Kunz, who may well be the one who coined them. Kunz had a gift for formulating precise concepts and giving them incisive Latin names (he later came up with the term bellum legale) [53]; the phrases we are concerned with appear in an article [54] he published in 1934 and a book that followed in 1935 [55]. Two years later, Alfred Verdross used the term jus in bello in exactly the same way as Kunz, placing it in parentheses after the word Kriegsrecht in his handbook on public international law [56].

The chapter on recourse to force was published only in the second edition, and here the term jus ad bellum appeared [57]. Around the same time, R. Regout made frequent use of both terms in his book on the doctrine of just war [58], making it clear from the outset that they reflected a fundamental distinction, and W. Ballis followed suit [59]. It is impossible to say whether these were independent developments or otherwise. Interestingly enough, neither term can be found in the texts produced by other major publicists during the interwar years, nor, according to our investigations, were they used in the courses on war and peace given at the The Hague Academy of International Law or in any other courses.

The breakthrough occurred only after the Second World War, when Paul Guggenheim, another disciple of the School of Vienna, drew the terminological distinction in one of the first major international law treatises of the postwar era [60]. A number of monographs subsequently took up the terms [61], which soon gained widespread acceptance and were launched on their exceptionally successful career. In a thesis written under Guggenheim’s supervision and published in 1956, Kotzsch gave them pride of place, treating them in the manner to which we have grown accustomed and which we now take for granted. [62] This article, the product of the author’s curiosity and of research carried out for another study [63], does not claim to provide a complete overview of the emergence of the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Indeed, there would be a lot more to say: many omissions would need to be remedied, and many imprecise points clarified. T

he purpose here is simply to shed some light on the origin of those terms and to dispel the general illusion that they have been used since earliest times. This false impression and the fact that so little is known on the subject, even by specialists, make this a fascinating field of research that yields surprising results.

Notes :

Original: French1. Jus ad bellum refers to the conditions under which one may resort to war or to force in general; jus in bello governs the conduct of belligerents during a war, and in a broader sense comprises the rights and obligations of neutral parties as well.2. P. Haggenmacher, Grotius et la doctrine de la guerre juste, Paris, 1983, pp. 250 ff. and 597 ff., and “Mutations du concept de guerre juste de Grotius à Kant”, Cahiers de philosophie politique et juridique, No. 10, 1986, pp. 117-122. 3. There is an abundant literature on the concept of just war. For the Graeco-Roman period in particular, see S. Clavadetscher-Thürlemann, Polemos dikaios und bellum iustum: Versuch einer Ideengeschichte, Zurich, 1985; M. Mantovani, Bellum iustum: Die Idee des gerechten Krieges in der römischen Kaiserzeit, Bern/Frankfurt am Main, 1990; S. Albert, Bellum iustum: Die Theorie des gerechten Krieges und ihre praktische Bedeutung für die auswärtigen Auseinandersetzungen Roms in republikanischer Zeit, Lassleben, 1980; H. Hausmaninger, “Bellum iustum und iusta causa belli in älteren römischen Recht”, Oesterreichische Zeitschrift für öffentliches Recht, 1961, Vol. 11, pp. 335 ff. For the Middle Ages in particular, see F.H. Russell, The just war in the Middle Ages, Cambridge/London, 1975; G. Hubrecht, “La guerre juste dans la doctrine chrétienne, des origines au milieu du XVIe siècle”, Recueil de la Société Jean Bodin, 1961, Vol. 15, pp. 107 ff.; J. Salvioli, Le concept de la guerre juste d’après les écrivains antérieurs à Grotius, 2nd ed., Paris, 1918; A. Vanderpol, La doctrine scolastique du droit de la guerre, Paris, 1925, p. 28 ff., and Le droit de la guerre d’après les théologiens et les canonistes du Moyen Age, Paris/Brussels, 1911; G. Beesterm-Iler, Thomas von Aquin und der gerechte Krieg: Friedensethik im theologischen Kontext der Summa Theologica, Cologne, 1990.On the notion of just war in general, see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit.; J.B. Elshtain, The just war theory, Oxford/Cambridge (Mass.), 1992; R. Regout, La doctrine de la guerre juste de Saint Augustin à nos jours, Paris, 1935; D. Beaufort, La guerre comme instrument de secours ou de punition, La Haye, 1933; M. Walzer, Just and unjust wars: A moral argument with historical illustrations, 2nd ed., New York, 1992; Y. de la Brière, Le droit de juste guerre, Paris, 1938; G.I.A.D. Draper, “The just war doctrine”, Yale Law Journal, Vol. 86, 1978, pp. 370 ff.; K. Szetelnicki, Bellum iustum in der katholischen Tradition, Fribourg, 1992.On the relationship with the Muslim doctrine of war, see J.T. Johnson, Just war and Jihad: Historical and theoretical perspectives on war and peace in Western and Islamic tradition, New York/London, 1991; R. Steinweg, Der gerechte Krieg: Christentum, Islam, Marxismus, Frankfurt am Main, 1980.4. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 457 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 108-109.5. Grotius, De iure belli ac pacis (1625), Book II, chap. I, 2, 1. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 549 ff.6. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 457 ff., 547 ff., and 568 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 110-113.7. Grotius, op. cit., Book III, chaps. XI-XVI (see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 600 ff.).8. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 600 ff.9. The rule limiting the competence to wage war to the public authorities (i.e. the sovereign) is affirmed in an oft-quoted passage of St Thomas Aquinas which sets out the three prerequisites for such competence: auctoritas principis, justa causa and recta intentio (Summa theologica, II, II, 40, 1). See O. Schilling, Das Völkerrecht nach Thomas von Aquin, Freiburg im Breisgau/Berlin, 1919. On recta intentio, see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 401 ff.10. See below.11. Grotius, op. cit., prolegomena, para. 28: “Ego cum ob eas, quas jam dixi, rationes, compertissimum haberem, esse aliquod inter populos ius commune, quod & ad bella & in bellis valeret...”. See also Book I, chap. I, 3, 1: “De iure belli cum inscribimus hanc tractationem, primum hoc ipsum intelligimus, quod dictum jam est, sitne bellum aliquod iustum, & deinde quid in bellum iustum sit”. (In giving our treatise the title The law of war, we first wish to examine, as we have said, whether war can be just and what is just in war. — ICRC translation.)12. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 601.13. Haggenmacher, “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 113-117.14. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 599 and 605 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 117 ff.15. On this dichotomy, see Haggenmacher, “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 107-108.16. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 599.17. De iure belli relectiones, Nos. 15 ff. (lawful motives for war) and Nos. 34 ff. (just limits in the law of war). See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 171-172 and 611.18. Jus gentium methodo scientifica pertractatum (1749), paras. 888 ff. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 607-608, and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 118-189.19. Le droit des gens (1758), Vol. III, chap. VIII. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 609-610, and “Mutations”, art. cit., p. 119.20. Metaphysik der Sitten, Rechtslehre, para. 53.21. As N. Politis puts it with his usual elegance in Les nouvelles tendances du droit international (Paris, 1927, pp. 100-101): “Sovereignty killed the theory of justum bellum. The States’ assertion that they did not have to account for their deeds led them to claim the right to use the force at their disposal as they saw fit” — ICRC translation).22. H. Wehberg, The outlawry of war, New York, 1931, and “La mise de la guerre hors la loi”, Recueil des Cours de l’Académie de droit international de La Haye (RCADI), 1928-IV, Vol. 24, pp. 146 ff.; C.C. Morrison, The outlawry of war: A constructive policy for world peace, Chicago, 1927; and Q. Wright, “The outlawry of war”, American Journal of International Law (AJIL), 1925, Vol. 19, pp. 76 ff.23. See for example Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei, I, 1, and Epistula CXXXVI.24. Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei, I, 1; I, 6; XIX, 23.25. Ibid.26. Grotius, De iure praedae, chap. VII, art. III-IV.27. Ibid.28. Grotius, De iure belli ac pacis, Book III, chap. I, 1.29. P.C. Timbal (ed.), La guerre de Cent Ans vue à travers les registres du Parlement (1337-1369), Paris, 1961, p. 541.30. H. Knighton, Chronicle, Vol. II, London, 1985, p. 111. Also see the note of Edward III concerning the Ivo de Kerembars affair, in M.H. Keen, The laws of war in the Middle Ages, London/Toronto, 1965, p. 29, note 1.31. G. Baker of Swinbrook, Chronicon, Oxford, 1889, pp. 86, 96 and 154.32. M.H. Keen, “Treason trials under the law of arms”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series, 1962, Vol. 12, p. 96. See also the letter from N. Rishdon to the Duke of Burgundy, in Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 17.33. M. Hayez, “Un exemple de culture historique au XVe siècle: la Geste des nobles français”, Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’Ecole française de Rome, 1963, Vol. 75, p. 162; Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 1.34. See the cases of David Margnies vs Prévôt de Paris (Parlement de Paris, ca 1420) and of Jean de Melun vs Henry Pomfret (Parlement de Paris, 1365), in Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 18 and 260.35. S. Luce, Histoire de Bertrand du Guesclin et de son époque. La jeunesse de Bertrand du Guesclin, 1320-1364, Paris, 1876, pp. 600-603.36. J. de Bueil, Le Jouvencel, Vol. II, Paris, 1889, p. 91.37. P. Contamine, Guerre, état et société à la fin du Moyen Age. Etudes sur les armées des rois de France, 1337-1494, Paris/The Hague, 1972, p.187.38. G.F. de Martens, Précis du droit des gens moderne de l’Europe, 3rd ed., Gottingen, 1821, p. 462, quoting an author writing in 1745; C. Lüder, in F. Holtzendorff (ed.), Handbuch des Völkerrechts, Vol. IV, Hamburg, 1889, p. 254.39. For all these examples and others, see Contamine, Guerre, état et société, op. cit., pp. 187 ff.; Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 1 ff.; E. Audinet, “Les lois et coutumes de la guerre à l’époque de la guerre de Cent Ans”, Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, 1917, Vol. 9.40. Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 7-22. It was only in the sixteenth century, at the time of the School of Salamanca, that jus belli took on the meaning that it has today in public law. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 283.41. Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 10 ff. On the concept of jus gentium, see inter alia M. Voigt, Das ius naturale, aequum et bonum und ius gentium der Römer, 4 vol., Aalen, reprint, 1966 (1st ed., Leipzig, 1856-1875); G. Lombardi, Sul concetto di ius gentium, Milan, 1974; M. Kaser, Ius gentium, Cologne/Weimar, 1993; M. Lauria, “Ius gentium”, Mélanges P. Koschaker, Vol. I, Weimar, 1939, pp. 258 ff.; P. Frezza, “Ius gentium”, Revue internationale des droits de l’Antiquité, 1949, Vol. 2, pp. 259 ff.; Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 313 ff.42. History of Rome, Book II, 12, and Book XXXI, 30: “Esse enim quaedam belli jura, quae ut facere ita pati sit fas”.43. A.G. Heffter, Le droit international de l’Europe, 4th ed., Berlin/Paris, 1883, p. 260.44. Histories, Book V, 9, 11.45. E. Nys, Les origines du droit international, Bruxelles/Paris, 1894, p. 208.46. See for example R. Ward, An enquiry into the foundations and history of the law of nations in Europe, Vol. II, London, 1795, p. 165; and R. Phillimore, Commentaries upon international law, Vol. II, London, 1857, p. 141.47. See for example de Martens, Précis du droit, op. cit., p. 461, para. 270, “Loix de la guerre”.48. See Actes et documents relatifs au programme de la Conférence de la Paix, The Hague, 1899; and Actes et documents: Deuxième Conférence internationale de la Paix, La Haye, 15 juin-18 octobre 1907, 3 vol., The Hague, 1907.49. G. Enriques, “Considerazioni sulla teoria della guerra nel diritto internazionale”, Rivista di diritto internazionale, 1928, Vol. 20, p. 172.50. H. Keydel, Das Recht zum Kriege im Völkerrecht, Frankfurter Abhandlungen zum moderne Völkerrecht, No. 24, Leipzig, 1931, p. 27.51. K. Strupp, “Les règles générales du droit de la paix”, RCADI, 1934-I, Vol. 47, p. 263 ff.52. On the Vienna neopositivist school of philosophy, see V. Kraft, Der Wiener Kreis: Der Ursprung des Neopositivismus, 2nd ed., Vienna/New York, 1968. On the legal school of Vienna, see J. Kunz, The changing law of nations, Toledo, 1968, pp. 59 ff.; and J. Stone, The province and function of law, Cambridge (Mass.), 1950, pp. 91 ff.53. “Bellum justum and bellum legale”, AJIL, 1951, Vol. 45, pp. 528 ff.54. “Plus de lois de guerre?”, Revue générale de droit international public (RGDIP), Vol. 41, 1934, p. 22.55. Kriegsrecht und Neutralitätsrecht, Vienna, 1935, pp. 1-2.56. Völkerrecht, Berlin, 1937, p. 289.57. Völkerrecht, 2nd ed., Berlin, 1950, p. 337.58. La doctrine de la guerre juste de saint Augustin à nos jours, Paris, 1935,pp. 15 ff.59. The legal position of war: Changes in its practice and theory from Plato to Vattel, The Hague, 1937, p. 2.60. P. Guggenheim, Lehrbuch des Völkerrechts, Vol. II, Basel, 1949, p. 778.61. See for example F. Grob, The relativity of war and peace, New Haven, 1949, pp. 161 and 183-185.62. The concept of war in contemporary history and international law, Geneva, 1956, pp. 84 ff.63. A contribution to the new edition of the Dictionnaire de droit international, edited by Jean Salmon and Eric David.

The august solemnity of Latin confers on the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello [1] the misleading appearance of being centuries old. In fact, these expressions were only coined at the time of the League of Nations and were rarely used in doctrine or practice until after the Second World War, in the late 1940s to be precise. This article seeks to chart their emergence.The doctrine of just warThe terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello did not exist in the Romanist and scholastic traditions. They were unknown to the canon and civil lawyers of the Middle Ages (glossarists, counsellors, ultramontanes, doctors juris utriusque, etc.), as they were to the classical authorities on international law (the School of Salamanca, Ayala, Belli, Gentili, Grotius, etc.). In neither period, moreover, was there a separation between two sets of rules — one ad bellum, the other in bello. [2]From earliest times, the Western tradition sought to place war in a legal framework by formulating a doctrine of just war [3]. The aim was to reconcile might and right, Sein and Sollen, by making the former serve the latter, or by curtailing might with right. On the basis of those premises, war was seen as a just response to unprovoked aggression, and more generally as the ultimate means for restoring a right that had been violated (consecutio juris) [4] or for punishing the offender [5]. The material causes for which a just war could be waged fell into four categories: defence, recuperation of property, recovery of debts and punishment. An act of war was considered lawful if it was just; and it was considered just if it met the conditions enumerated above.In the doctrine of bellum justum, therefore, legal analysis bore exclusively on the act of resorting to war, and more particularly on the causes pursued.

War was viewed from the subjective angle as a concrete act carried out by a specific belligerent for specific reasons, and such an act brought into being a legal regime that reflected the validity of the causes invoked or, so to speak, the belligerent’s right to resort to force. This meant that war was not seen as a de facto situation to which the same set of rules applied in all cases. In other words, there was no general jus in bello; the rights and obligations of belligerents were unequal and depended exclusively on the causes which they claimed to be pursuing and on the material justness of those causes. [6]

Thus, for example, Grotius’s temperamenta belli (restrictions on warfare), which it is tempting to equate with contemporary jus in bello, applied only to belligerents resorting to war for a just cause [7]; they broadened the concept of just war while defining its limits. Here, too, everything revolved around the notion of just cause. A belligerent without a just cause had no rights; he was simply a criminal who might beexecuted.

Consequently, no legal restraints could be imposed on his behaviour. For these reasons, there was no room for jus in bello as we understand it today, that is, a body of independent, objective and suprapersonal rules applying to all belligerents alike and governing the conduct of hostilities in a de facto situation [8]. This explains why both the term jus in bello and the concept to which it refers are absent from the classical texts.

As for the term jus ad bellum, its absence is more surprising. However, the simple right to wage war that was vested in public authorities was also irrelevant in the doctrine of bellum justum [9]. Legal analysis looked deeper, focusing instead on causes and hence on the lawfulness of resorting to war. Moreover, the predominance of ad bellum considerations in general over the in bello aspect made it impossible even to conceive of such terms, whose existence would have implied a more extensive, evenly balanced and fully articulated development of two mutually exclusive branches of the law [10].

We are reminded of the early philosophers’ theory whereby a term or a concept can come into existence only in relation to its absolute opposite. They claimed, for example, that ugliness existed only in relation to beauty; it could not be conceived of except in contrast to beauty.

Although the time was clearly not ripe for the emergence of the terms that concern us here, they sometimes crept in, used in a non-technical sense far removed from their modern meaning. Grotius, for instance, wrote that he was “fully convinced (...) that there is a law common to all nations governing both recourse to war and the conduct of warfare...” [11]. This law ad bella and in bellis obviously remained subordinate to the doctrine of just war [12]. To sum up, the subjective notion of the right to wage war in pursuit of certain causes precluded the emergence of an independent jus in bello; at the same time, however, the doctrine of lawful causes for waging war inhibited the affirmation of the simple right to make war (jus ad bellum). In such a system, both concepts lay outside the scope of the law, which was concerned with antecedent issues.

War as a de facto situation.

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the doctrine of just war lost ground to the idea that States had discretionary powers to wage war and that those powers could be used as a means of pursuing national policy. That was the era of raison d’Etat. This concept of war became permanently entrenched in the nineteenth century, in parallel with the erosion of the concept of war as a just act. War was now seen as a de facto and intellectually neutral situation [13]. Quite logically, the result was a major shift in the legal emphasis from the subjective lawfulness of resorting to war to the rights and duties relating to hostilities as such, in other words to rights and duties durante bello [14]. This new edifice appears to be a mirror image of the previous one. A system based on the material lawfulness of war (war as a sanction) gave way to a system focusing on its formal regulation (rules pertaining to the opening of hostilities and the effects of war) [15]. To quote an eminent specialist on the subject: “Now that the field of vision had been restricted, greater attention could be paid to the conduct of hostilities: for owing to this indifference [to the causes of war], armed violence came to be seen first and foremost as a process to be regulated in itself, regardless of its causes, motives and ends.” [16]

This opened the door to jus in bello as it is understood today. The distinction which Vitoria had already begun to make between lawful reasons for resorting to war and just limits in the law of war [17] was upheld by Wolff, the first to see rights and duties durante bello as being independent of the underlying causes of war [18], and was later firmly established by Vattel, who incorporated into the law of nations a series of rules setting legal restrictions on means of warfare [19]. Kant made an explicit and modern distinction between the two branches of the law (Recht zum Krieg and Recht im Kriege) [20], but neither he nor any of the other authors mentioned used the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello. The explanation for this lies in the lack of any doctrinal need to draw a conceptual distinction between the two branches of the law rather than in random developments of terminology or the decline of Latin.

The fact is that for reasons that were different in nature but identical as to their effect, the mere competence to resort to war (jus ad bellum) aroused no more legal interest than it had previously. As one of the sovereign’s absolute and discretionary powers [21], it was seen as the cornerstone of the rules of law relating to war, their logical prius, and thus basically remained an implicit dogma. Legal endeavours had focused entirely on the formalities to be observed in initiating hostilities and on the respective rights and obligations of belligerents, that is to say on matters subsequent to the subjective right to resort to war. Yet the term jus in bello was still not used. The lack of any opposition or equivalence between the two branches of the law prevented the emergence of such a term, which could only come into existence when the two aspects of war assumed approximately equal importance and it became necessary to underline the distinction between them.

It was at the time of the League of Nations that the two branches came to be considered on an equal footing and found their place in positive law. In the expression of the time, the aim was to “outlaw war” [22]. The former absolute power to resort to war was replaced by the rules of jus contra bellum. From then on, the problem of recourse to force was at the centre of legal concerns, standing in opposition to law in bello. The theoretical distinction between laws aimed at preventing war and the laws and customs of warfare was thus clearly established. All that remained to be done was to find appropriate terminological expression for this distinction, which had finally crystallized under the pressure of history.

The terminological aspect

Neither in the Middle Ages nor in the Age of Enlightenment did the law lack terms for what is now known as jus in bello. At least certain analogies can be drawn providing the conceptual differences outlined above are taken into account. Many texts from these periods contain terms such as jus belli [23], usus in bello [24], mos et consuetudo bellorum [25], modus belli gerendi [26], forma belli gerendi [27], quid quantumque in bello liceat et quibus modis [28], jus armorum [29], lex armorum [30], jus militare [31], jura et usus armorum [32], droiz de guerre [33], droit d’armes [34], drois, usaiges et coustumes d’armes [35], usance de guerre [36], droit et usage d’armes [37], Kriegsmanier [38], etc [39]. Not all these terms pertain to public international law as we understand it today: they did not apply only to armies set up under public authority. Jus armorum was the professional code for warriors [40] — knights, for example — and constitutes jus gentium. [41]

One important expression in the context of public international law is jura belli, which can be traced back to Livy[42]. In the nineteenth century it was sometimes used to mean jus in bello in the modern sense (Heffter used it this way in his influential handbook) [43]. The Latin terms jura belli and jus belli both seem to have been derived from the Greek expression “oi tou polemou nomoi” used by Polybius [44]. The English expression “laws of war” is also quite old. During the reign of Charles I, the Earl of Essex decreed the Laws and ordinances of war governing the conduct of the parliamentary forces during the civil war that brought Cromwell to power [45]. The term can be found in the literature as well [46]. In French, the expression lois de la guerre rapidly gained acceptance. [47]

It is extremely rare to find the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello used before 1930. Neither was mentioned during the 1899 and 1907 Peace Conferences, among whose aims was codification of the law of war [48]. Enriques used the term jus ad bellum in 1928, having apparently invented it on the spot to serve a specific need[49]. Keydel drew a clear distinction between the two branches of the law in a well-researched thesis on recourse to war published in 1931 in a scholarly review edited by Professor Strupp, but did not use the terms in question [50]. Keydel, like Strupp himself [51], diligently enumerated all the Latin words and expressions relating to the matter. It may be concluded, therefore, that up to the early 1930s the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello had no currency.

They began to gain recognition towards the middle of the decade, in particular, it would seem, at the prompting of the School of Vienna. [52] Among the first to use these terms was Josef Kunz, who may well be the one who coined them. Kunz had a gift for formulating precise concepts and giving them incisive Latin names (he later came up with the term bellum legale) [53]; the phrases we are concerned with appear in an article [54] he published in 1934 and a book that followed in 1935 [55]. Two years later, Alfred Verdross used the term jus in bello in exactly the same way as Kunz, placing it in parentheses after the word Kriegsrecht in his handbook on public international law [56].

The chapter on recourse to force was published only in the second edition, and here the term jus ad bellum appeared [57]. Around the same time, R. Regout made frequent use of both terms in his book on the doctrine of just war [58], making it clear from the outset that they reflected a fundamental distinction, and W. Ballis followed suit [59]. It is impossible to say whether these were independent developments or otherwise. Interestingly enough, neither term can be found in the texts produced by other major publicists during the interwar years, nor, according to our investigations, were they used in the courses on war and peace given at the The Hague Academy of International Law or in any other courses.

The breakthrough occurred only after the Second World War, when Paul Guggenheim, another disciple of the School of Vienna, drew the terminological distinction in one of the first major international law treatises of the postwar era [60]. A number of monographs subsequently took up the terms [61], which soon gained widespread acceptance and were launched on their exceptionally successful career. In a thesis written under Guggenheim’s supervision and published in 1956, Kotzsch gave them pride of place, treating them in the manner to which we have grown accustomed and which we now take for granted. [62] This article, the product of the author’s curiosity and of research carried out for another study [63], does not claim to provide a complete overview of the emergence of the terms jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Indeed, there would be a lot more to say: many omissions would need to be remedied, and many imprecise points clarified. T

he purpose here is simply to shed some light on the origin of those terms and to dispel the general illusion that they have been used since earliest times. This false impression and the fact that so little is known on the subject, even by specialists, make this a fascinating field of research that yields surprising results.

Notes :

Original: French1. Jus ad bellum refers to the conditions under which one may resort to war or to force in general; jus in bello governs the conduct of belligerents during a war, and in a broader sense comprises the rights and obligations of neutral parties as well.2. P. Haggenmacher, Grotius et la doctrine de la guerre juste, Paris, 1983, pp. 250 ff. and 597 ff., and “Mutations du concept de guerre juste de Grotius à Kant”, Cahiers de philosophie politique et juridique, No. 10, 1986, pp. 117-122. 3. There is an abundant literature on the concept of just war. For the Graeco-Roman period in particular, see S. Clavadetscher-Thürlemann, Polemos dikaios und bellum iustum: Versuch einer Ideengeschichte, Zurich, 1985; M. Mantovani, Bellum iustum: Die Idee des gerechten Krieges in der römischen Kaiserzeit, Bern/Frankfurt am Main, 1990; S. Albert, Bellum iustum: Die Theorie des gerechten Krieges und ihre praktische Bedeutung für die auswärtigen Auseinandersetzungen Roms in republikanischer Zeit, Lassleben, 1980; H. Hausmaninger, “Bellum iustum und iusta causa belli in älteren römischen Recht”, Oesterreichische Zeitschrift für öffentliches Recht, 1961, Vol. 11, pp. 335 ff. For the Middle Ages in particular, see F.H. Russell, The just war in the Middle Ages, Cambridge/London, 1975; G. Hubrecht, “La guerre juste dans la doctrine chrétienne, des origines au milieu du XVIe siècle”, Recueil de la Société Jean Bodin, 1961, Vol. 15, pp. 107 ff.; J. Salvioli, Le concept de la guerre juste d’après les écrivains antérieurs à Grotius, 2nd ed., Paris, 1918; A. Vanderpol, La doctrine scolastique du droit de la guerre, Paris, 1925, p. 28 ff., and Le droit de la guerre d’après les théologiens et les canonistes du Moyen Age, Paris/Brussels, 1911; G. Beesterm-Iler, Thomas von Aquin und der gerechte Krieg: Friedensethik im theologischen Kontext der Summa Theologica, Cologne, 1990.On the notion of just war in general, see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit.; J.B. Elshtain, The just war theory, Oxford/Cambridge (Mass.), 1992; R. Regout, La doctrine de la guerre juste de Saint Augustin à nos jours, Paris, 1935; D. Beaufort, La guerre comme instrument de secours ou de punition, La Haye, 1933; M. Walzer, Just and unjust wars: A moral argument with historical illustrations, 2nd ed., New York, 1992; Y. de la Brière, Le droit de juste guerre, Paris, 1938; G.I.A.D. Draper, “The just war doctrine”, Yale Law Journal, Vol. 86, 1978, pp. 370 ff.; K. Szetelnicki, Bellum iustum in der katholischen Tradition, Fribourg, 1992.On the relationship with the Muslim doctrine of war, see J.T. Johnson, Just war and Jihad: Historical and theoretical perspectives on war and peace in Western and Islamic tradition, New York/London, 1991; R. Steinweg, Der gerechte Krieg: Christentum, Islam, Marxismus, Frankfurt am Main, 1980.4. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 457 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 108-109.5. Grotius, De iure belli ac pacis (1625), Book II, chap. I, 2, 1. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 549 ff.6. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 457 ff., 547 ff., and 568 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 110-113.7. Grotius, op. cit., Book III, chaps. XI-XVI (see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 600 ff.).8. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 600 ff.9. The rule limiting the competence to wage war to the public authorities (i.e. the sovereign) is affirmed in an oft-quoted passage of St Thomas Aquinas which sets out the three prerequisites for such competence: auctoritas principis, justa causa and recta intentio (Summa theologica, II, II, 40, 1). See O. Schilling, Das Völkerrecht nach Thomas von Aquin, Freiburg im Breisgau/Berlin, 1919. On recta intentio, see Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 401 ff.10. See below.11. Grotius, op. cit., prolegomena, para. 28: “Ego cum ob eas, quas jam dixi, rationes, compertissimum haberem, esse aliquod inter populos ius commune, quod & ad bella & in bellis valeret...”. See also Book I, chap. I, 3, 1: “De iure belli cum inscribimus hanc tractationem, primum hoc ipsum intelligimus, quod dictum jam est, sitne bellum aliquod iustum, & deinde quid in bellum iustum sit”. (In giving our treatise the title The law of war, we first wish to examine, as we have said, whether war can be just and what is just in war. — ICRC translation.)12. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 601.13. Haggenmacher, “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 113-117.14. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 599 and 605 ff., and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 117 ff.15. On this dichotomy, see Haggenmacher, “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 107-108.16. Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 599.17. De iure belli relectiones, Nos. 15 ff. (lawful motives for war) and Nos. 34 ff. (just limits in the law of war). See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 171-172 and 611.18. Jus gentium methodo scientifica pertractatum (1749), paras. 888 ff. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 607-608, and “Mutations”, art. cit., pp. 118-189.19. Le droit des gens (1758), Vol. III, chap. VIII. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 609-610, and “Mutations”, art. cit., p. 119.20. Metaphysik der Sitten, Rechtslehre, para. 53.21. As N. Politis puts it with his usual elegance in Les nouvelles tendances du droit international (Paris, 1927, pp. 100-101): “Sovereignty killed the theory of justum bellum. The States’ assertion that they did not have to account for their deeds led them to claim the right to use the force at their disposal as they saw fit” — ICRC translation).22. H. Wehberg, The outlawry of war, New York, 1931, and “La mise de la guerre hors la loi”, Recueil des Cours de l’Académie de droit international de La Haye (RCADI), 1928-IV, Vol. 24, pp. 146 ff.; C.C. Morrison, The outlawry of war: A constructive policy for world peace, Chicago, 1927; and Q. Wright, “The outlawry of war”, American Journal of International Law (AJIL), 1925, Vol. 19, pp. 76 ff.23. See for example Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei, I, 1, and Epistula CXXXVI.24. Saint Augustine, De civitate Dei, I, 1; I, 6; XIX, 23.25. Ibid.26. Grotius, De iure praedae, chap. VII, art. III-IV.27. Ibid.28. Grotius, De iure belli ac pacis, Book III, chap. I, 1.29. P.C. Timbal (ed.), La guerre de Cent Ans vue à travers les registres du Parlement (1337-1369), Paris, 1961, p. 541.30. H. Knighton, Chronicle, Vol. II, London, 1985, p. 111. Also see the note of Edward III concerning the Ivo de Kerembars affair, in M.H. Keen, The laws of war in the Middle Ages, London/Toronto, 1965, p. 29, note 1.31. G. Baker of Swinbrook, Chronicon, Oxford, 1889, pp. 86, 96 and 154.32. M.H. Keen, “Treason trials under the law of arms”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series, 1962, Vol. 12, p. 96. See also the letter from N. Rishdon to the Duke of Burgundy, in Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 17.33. M. Hayez, “Un exemple de culture historique au XVe siècle: la Geste des nobles français”, Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’Ecole française de Rome, 1963, Vol. 75, p. 162; Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 1.34. See the cases of David Margnies vs Prévôt de Paris (Parlement de Paris, ca 1420) and of Jean de Melun vs Henry Pomfret (Parlement de Paris, 1365), in Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 18 and 260.35. S. Luce, Histoire de Bertrand du Guesclin et de son époque. La jeunesse de Bertrand du Guesclin, 1320-1364, Paris, 1876, pp. 600-603.36. J. de Bueil, Le Jouvencel, Vol. II, Paris, 1889, p. 91.37. P. Contamine, Guerre, état et société à la fin du Moyen Age. Etudes sur les armées des rois de France, 1337-1494, Paris/The Hague, 1972, p.187.38. G.F. de Martens, Précis du droit des gens moderne de l’Europe, 3rd ed., Gottingen, 1821, p. 462, quoting an author writing in 1745; C. Lüder, in F. Holtzendorff (ed.), Handbuch des Völkerrechts, Vol. IV, Hamburg, 1889, p. 254.39. For all these examples and others, see Contamine, Guerre, état et société, op. cit., pp. 187 ff.; Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 1 ff.; E. Audinet, “Les lois et coutumes de la guerre à l’époque de la guerre de Cent Ans”, Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, 1917, Vol. 9.40. Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., pp. 7-22. It was only in the sixteenth century, at the time of the School of Salamanca, that jus belli took on the meaning that it has today in public law. See Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., p. 283.41. Keen, The laws of war, op. cit., p. 10 ff. On the concept of jus gentium, see inter alia M. Voigt, Das ius naturale, aequum et bonum und ius gentium der Römer, 4 vol., Aalen, reprint, 1966 (1st ed., Leipzig, 1856-1875); G. Lombardi, Sul concetto di ius gentium, Milan, 1974; M. Kaser, Ius gentium, Cologne/Weimar, 1993; M. Lauria, “Ius gentium”, Mélanges P. Koschaker, Vol. I, Weimar, 1939, pp. 258 ff.; P. Frezza, “Ius gentium”, Revue internationale des droits de l’Antiquité, 1949, Vol. 2, pp. 259 ff.; Haggenmacher, Grotius, op. cit., pp. 313 ff.42. History of Rome, Book II, 12, and Book XXXI, 30: “Esse enim quaedam belli jura, quae ut facere ita pati sit fas”.43. A.G. Heffter, Le droit international de l’Europe, 4th ed., Berlin/Paris, 1883, p. 260.44. Histories, Book V, 9, 11.45. E. Nys, Les origines du droit international, Bruxelles/Paris, 1894, p. 208.46. See for example R. Ward, An enquiry into the foundations and history of the law of nations in Europe, Vol. II, London, 1795, p. 165; and R. Phillimore, Commentaries upon international law, Vol. II, London, 1857, p. 141.47. See for example de Martens, Précis du droit, op. cit., p. 461, para. 270, “Loix de la guerre”.48. See Actes et documents relatifs au programme de la Conférence de la Paix, The Hague, 1899; and Actes et documents: Deuxième Conférence internationale de la Paix, La Haye, 15 juin-18 octobre 1907, 3 vol., The Hague, 1907.49. G. Enriques, “Considerazioni sulla teoria della guerra nel diritto internazionale”, Rivista di diritto internazionale, 1928, Vol. 20, p. 172.50. H. Keydel, Das Recht zum Kriege im Völkerrecht, Frankfurter Abhandlungen zum moderne Völkerrecht, No. 24, Leipzig, 1931, p. 27.51. K. Strupp, “Les règles générales du droit de la paix”, RCADI, 1934-I, Vol. 47, p. 263 ff.52. On the Vienna neopositivist school of philosophy, see V. Kraft, Der Wiener Kreis: Der Ursprung des Neopositivismus, 2nd ed., Vienna/New York, 1968. On the legal school of Vienna, see J. Kunz, The changing law of nations, Toledo, 1968, pp. 59 ff.; and J. Stone, The province and function of law, Cambridge (Mass.), 1950, pp. 91 ff.53. “Bellum justum and bellum legale”, AJIL, 1951, Vol. 45, pp. 528 ff.54. “Plus de lois de guerre?”, Revue générale de droit international public (RGDIP), Vol. 41, 1934, p. 22.55. Kriegsrecht und Neutralitätsrecht, Vienna, 1935, pp. 1-2.56. Völkerrecht, Berlin, 1937, p. 289.57. Völkerrecht, 2nd ed., Berlin, 1950, p. 337.58. La doctrine de la guerre juste de saint Augustin à nos jours, Paris, 1935,pp. 15 ff.59. The legal position of war: Changes in its practice and theory from Plato to Vattel, The Hague, 1937, p. 2.60. P. Guggenheim, Lehrbuch des Völkerrechts, Vol. II, Basel, 1949, p. 778.61. See for example F. Grob, The relativity of war and peace, New Haven, 1949, pp. 161 and 183-185.62. The concept of war in contemporary history and international law, Geneva, 1956, pp. 84 ff.63. A contribution to the new edition of the Dictionnaire de droit international, edited by Jean Salmon and Eric David.

Monday, February 18, 2008

PROPOSAL FOR A DEBATE:

Resolved that Canada’s Involvement in Afghanistan is Lawful

Proposed Teams:

1. For the Affirmative

John Manley

Derek Burney

Pamela Wallin

Alternate: Jack Granatstein

2. For the Negative

Lloyd Axworthy

Michael Byers

Eric Margolis

Alternate: Amir Attaran

Time and date: tba

Proposed Teams:

1. For the Affirmative

John Manley

Derek Burney

Pamela Wallin

Alternate: Jack Granatstein

2. For the Negative

Lloyd Axworthy

Michael Byers

Eric Margolis

Alternate: Amir Attaran

Time and date: tba

Sunday, February 17, 2008

J.L. Granatstein; Military Historian, American Apologist, Space Cadet

Who is this guy? Whoever he is, I don't think his grandiose ideas would play well at The Legion on Saturday night.